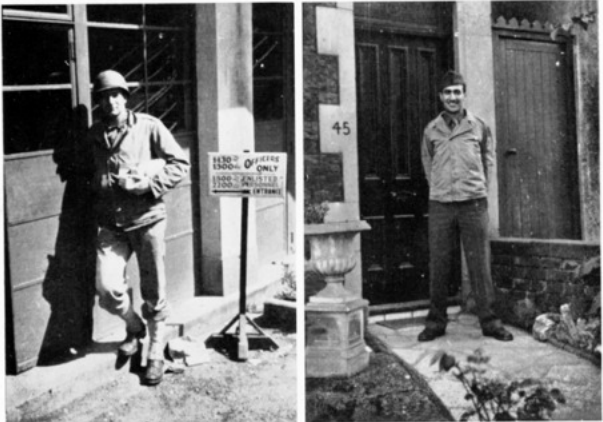

Otis F. Wollenberg was born in Pendleton, New York and graduated from North Tonawanda, New York High School in 1940. He was 20 years old when he was drafted to serve his country. The following are selected extracts an account of the 32nd Machine Records Unit (Mobile) written by its men, including Otis, and compiled by Snider Skinner in 1952. The memoir is called: ‘THE HISTORY OF THE 32ND MACHINE RECORDS UNIT (MOBILE) OR The First Million Cards Punched Are the Toughest!’ Further details about Otis F. Wollenberg are provided by his niece, Donna Burolla, who kindly gave me permission to reproduce this account.

The 32nd Machine Records Unit (Mobile)

“For the first time in the history of warfare the complicated procedure of accounting for personnel and battle casualties was put on a machine basis in World War II.

Realizing the need for a system to handle an unprecedented volume of personnel, the War Department started experimenting with the use of International Business Machines to accomplish the mission. Having proved successful in the early stages of build-up, a program was initiated to activate a number of fixed and mobile units for domestic and overseas service. The result was that the framework of this new type unit was rapidly established and the part it was to play in the great show written in a quiet but important role.

This all leads up to the activation on the 32nd MRU (M) at Governors Island, N.Y., on 5 August 1943. The first few months were spent studying, planning, getting harnessed to the job, and preparing for movement overseas.

Bristol, England (22 January, 1944)

The five months and thirteen days spent in Bristol were second in our affections only to our four months in New York City. It was the only overseas location where we were able to take part freely in social activities. In all future locations, the huge barrier of language was to be a serious handicap for most of us.

When we left the train at Temple Meads station, there was a great welcoming committee there to greet us. If I remember correctly, there was a total of four GI’s, including one staff sergeant, and four trucks. The English weather was upholding its age-old tradition by giving forth with the inevitable drizzle of rain. Sixty dampened, but no less excited, spirits climbed aboard the trucks and proceeded to their new home. As we rode through the city we glimpsed our first bomb damage, the calling card of Germany, which was to become so commonplace in the following two years.

Our new home was the Pollack House located at Clifton College in an area known as Clifton Downs, one of the most beautiful spots in Bristol. The College, previous to occupation by the First U.S. Army Headquarters, had been a boys’ school. The most famous landmark on the Downs was undoubtedly the Suspension Bridge. This bridge spanned a huge gorge at the bottom of which flowed the Bristol Avon. The sides of the gorge were solid rock. The English people have a fable which states that the gorge was caused by a couple of giants who moved a few rocks around during a little disagreement.

A few hours after our arrival, our trailers were set up on a rugby field in the rear of the Pollack House. This ideal arrangement lasted not more than a week. It seems that our generators operating twenty-four hours daily caused no little loss of sleep among our English neighbors. And so it was necessary to move our trailers to a new location across from the Bristol Zoo into the First Army motor pool. This meant that we had to walk quite a distance to work. The hike, however, soon assumed brighter aspects due to the presence of a WAAF barrage balloon post along the route.

Inspection

For an MRU, any inspection other than a minor one is certainly a very rare occurrence and any GI will tell you that a General’s inspection is anything but minor. As the English would say, ‘We had it.” No less a figure than the First Army’s Chief of Staff, Brigadier General W.B. Kean, did the honors. No nickel and dime stuff for the 32nd! After several attempts which were thwarted by slight showers, we finally managed a formation. There we were lined up in open ranks; and as the General and his entourage passed each man there was a timely present arms. I would like to describe the sensation felt by each individual as it came his turn to sweat out those stars but Mr. Webster, in writing his dictionary, did not take such circumstances into consideration.

It didn’t take long to get into the social swing-such as it was. A discovery here, a discovery there, and pretty soon we weren’t doing so badly. With the focal points being: Blackboy Hill, Old Market, and the Center, we found innumerable pleasant distractions from our work. Also necessary to complete this list of recreational places of interest, were: the American Red Cross, the Victoria Rooms, Crockers, St. James’s Park, the Ironmonger’s Daughter, the Odeon, the Green Lantern, the Freight Loader, the Kings Arms, the Princess, the Bee Hive, the Windsor Café, and just the plain Downs.

It was somewhat amusing to see some of the boys adopt certain English customs. One sight, not uncommon, was that of a couple of GI’s walking nonchalantly down the street eating chips from a greasy paper bag.

Early days in Bristol were busy ones with a group of 55 enlisted men and four officers trying for the first time to organize themselves into an efficient machine for its place in the Army. It was an anxious time, too, for everyone realized the approach of the storm about to break over Europe. We were more on the “in,” as it were, for many phases of the business at hand flashed lights upon the picture of things to come; but the actual date of D-Day was left to the speculation of the individual. There was much of it.

After about two months at the Pollack House, we moved into private billets in a section of the city called Henleaze. It was here that we experienced our most intimate contact with the English people because we were all living practically as charter members of our respective households. Although there were naturally a few instances which were none too harmonious, by far the greater number of us were extremely happy and contented with our adopted parents. When you stop to consider that we were actually forced upon these people, the amount of consideration which they bestowed upon us was wonderful. Many of us were pleasantly awakened by having breakfast brought to our bedside. Others received afternoon “tea” in a manner befitting nobility. The English people were required only to furnish us with sleeping and toilet facilities – any act beyond this they performed in order to make our stay more comfortable and aptly illustrated their generosity and kindness.

Moving into Private Houses

After a couple of months which seemed more like a couple of weeks, we left our homes and returned to the Pollack House (first floor this time). This time each shift was put into a separate room. Probably the most versatile room was the one known as the “kindergarten,” under the able influence and leadership of Professor John V. (You can’t be a good-time Charlie and get the work out) Griffis. The students, or members of the evening shift, learned a great deal about pin-ups, miniature air raids, and miscellaneous practical jokes. To illustrate the latter, one member of the institution awoke from a pleasant night’s rest to find his bed balanced precariously on a window ledge and surrounded by the startled eyes of the local citizens.

It was here that we lost our commanding officer, Capt. George Barnett, who had been with us since Governors Island. He was replaced by Major Glenn Summers who remains with us to this day as our commanding officer.

Our 32nd Machine Records Unit softball team won the First Army Headquarters championship for 1944 at Bristol, England. Our record at the end of the season was 11 wins and 0 losses. Our team was to get a trophy for winning the championship, but D-Day came off just about then and we became a winner without a trophy.

Moving Out

With the arrival of dawn, 6 June 1944, came the electrifying news flashes on all radios that the landings on the Normandy beaches of France were accomplished facts and the tremendous springboard of action accumulated during months of feverish preparation in England had thrown its first weight with a might heave. Little springs were released somewhere within the beings of all men, and so for the men in the 32nd. Tension eased and, undoubtedly, a prayer for continued success was in the heart of each of us. Then, work upon our assigned jobs continued and the spring began to coil.

Now the preparation for “moving out” so evident everywhere began to concentrate in the particular ways we were to be affected. A million things seemed to cry for attention and all had to be completed in the haze of uncertainty surround the preparation for a little D-Day of our own. The three shifts, into which our working days were divided, continued to pour out the detailed work assigned and, in addition, the vans and all vehicles had to be made waterproof with a putty like substance. We swarmed the underparts like so many ants, all busy plugging every crack. Each had to see to the marking of his equipment, checking and rechecking the numerous articles, besides stenciling name, rank, and serial number on his duffel bag and putting a common identification on its side and bottom. The great white star, marking all the vans, had to be carefully painted on the ascribed places. Meetings were held for last-minute instructions. There was the final reading of the Articles of War. The chaplain’s lecture was heard. Nothing was overlooked.

With all these preparations proceeding smoothly to a termination, official orders informed us that we would proceed to the staging area and from there to the port of embarkation by July 3. In the span of a day all last-minute adjustments were made and, after each man had stuffed his duffel bag until nothing more could be crammed inside, it seemed that all prescribed articles did have a place – a thing few would have believed possible.

Up until the time of departing from Bristol, fortune was with us. There was no restriction placed upon us, so that one last evening was ours to bid farewell to the city which had been so hospitable for almost six months. Although under orders not to divulge the next day’s departure, the undercurrent of expectancy betrayed itself.

All the men guessed that our destination lay in the south of England, but until arriving at Southampton, none but a few were certain. Many assumed this as the convoy train headed south from the Bristol station. We were approaching the most important phase of our careers.”

After D-Day

Otis landed on Utah Beach on 5th July 1944 moving through Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes and was in Weimar, Germany by VE Day from where they visited Buchenwald Concentration Camp. They were stationed in Le Harve at the time of VJ Day and as the 32nd MRU’s account finishes “At a little after two o’clock that same afternoon, the men of the 32nd climbed up the gangplank to board the liberty ship, SS. Archbishop Lamy. Several hours later they were easing out of Le Havre, leaving the ETO behind and heading for home.”

After returning from the war in 1945, Otis Wollenberg married his sweetheart, Evelyn A. Pagels, on June 15, 1946. In 1947 he went to work for Sylvania in Buffalo, New York transferring to El Paso, Texas in 1972 and retiring in 1983 as a specification writer after 36 years with the company, which is now Verizon. Evelyn died in 1994 and Otis in 2003; both interned at Fort Bliss National Cemetery, Texas.

We’d love to hear your own stories. Please get in touch with us by emailing YanksinBristol@gmail.com

Copyright © 2025 – YanksInBristol.co.uk – All rights reserved.