This remarkable and beautifully written account of a G.I.’s time in Brislington was brought to my attention by Stella Man of Glenside Hospital Museum who found it in their archives after I visited. The museum is highly recommend for its history as a both psychiatric and Great War hospital (Open Wednesday 10am – 1pm, Saturday 10am – 4pm).

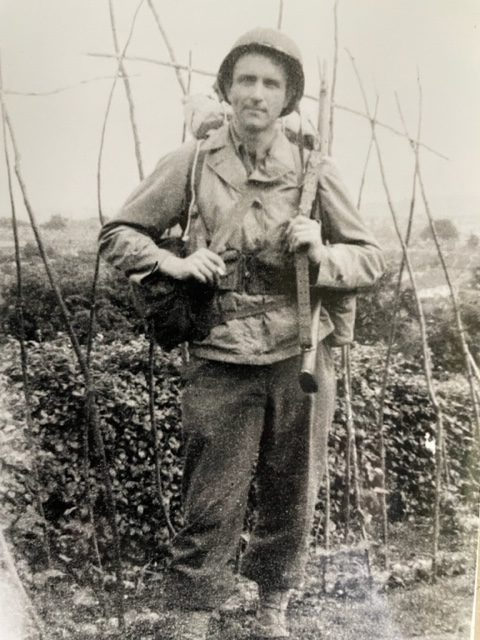

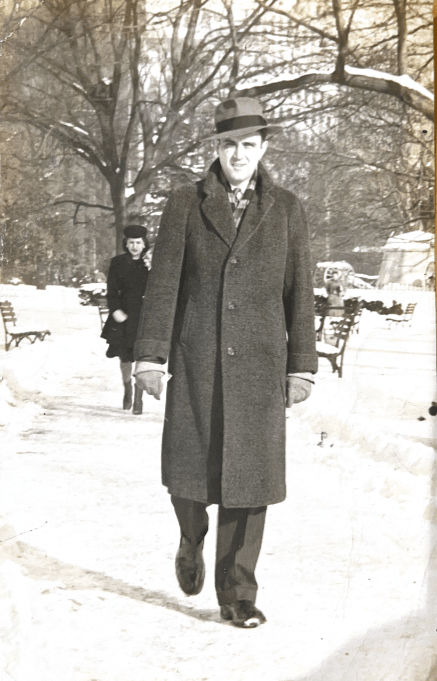

Eugene S. Norton was born in New Jersey in September 1916 and grew up in Morris County. After attending university for four years, studying English and Philosophy, he enlisted in August 1942 as a single man without dependents. Frustratingly, his memoirs don’t mention his unit or even his regiment but he was a warrant officer in the U.S Army.

He was a self-confessed Anglophile and lover of English literature as his first letter home from Bristol demonstrates:

“As I stepped onto the platform at Temple Meads, an overpowering urge to understand England arose within me. I realized that it would be impossible to learn first-hand in a limited time period the attributes of life that composed an England…

I saw sign above the railway bridge which stated, ‘George Beer Ltd’. These three words addressing the satisfying of England should be rooted in knowing the people, how they thought and worshipped, the events they enjoyed, and how their daily lives were lived… To paraphrase an old Roman slogan, I would be ‘a Yank in England who would do as the English do’”.

Eugene had left New York in late 1943 on the luxury liner Mauretania with 18,000 others. As with many Americans, he was unimpressed by the cuisine: “food was not of the best; I managed to exist on candy bars”.

After docking in Greenock, they took the train down to Birmingham: “As the train sped southward, my face remained glued to the window; my eyes riveted on the passing landscape, quiet and peaceful in green luxury like pages of English novels once read”.

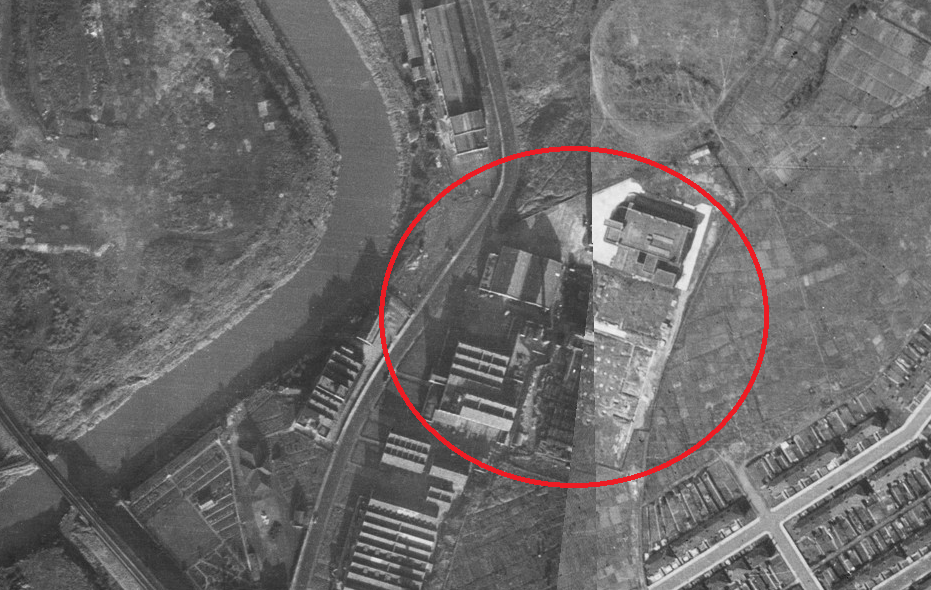

After a short stay in Birmingham, Eugene took the train down to Bristol. “My permanent assignment was made and several of us departed for our final destination in England, ADSEC Headquarters in Brislington. Arriving at Temple Meads Station, we were trucked to and billeted in the Co-op bakery on Whitby Street.”

Eugene doesn’t mention what his unit was or did and there may be a good reason for that. The bakery was built by the US Army as a cover for all the ADSEC activities. The ‘Advanced Section, Communications Zone, (European Theatre of Operations)’ was involved in all the practical logistics to do with the Normandy invasion. Within the bakery wer thousands of maps of the planned battle areas in Normandy as well as 20 million Francs. Volunteering as a guard meant that Eugene would have an 8-hour shift without relief before almost two free days to the next tour. Until his billet was ready, he would be staying in a temporary camp at the bakery.

The day soon came when he was driven to his billet and as he turned the corner into Allison Road he noticed a small farm, several bombed out houses and a concrete road. He ascended the steps to his new home, his driver carrying his paillasse (camp bed) with difficulty. As the door was opened by “a woman of a delicate manner”, he felt like “an intruder [who] would shortly trespass on the privacy of a family. What would this mean to the family who had no recourse but to accept me?”

Nell Wilson showed him to his room. “It was small, on the second floor, bare with the exception of a cabinet for my clothes”. Shortly after, “a voice called and asked if I would care to have ‘a spot of tea’”. Tea had been delayed so he could meet the rest of the family: husband Roy (“former soldier with a military air”); Jean (“a lovely girl of twelve”) and Bryan (a lad of five)”. They chatted “aimlessly about a thousand items of trivia; life in America” and many other topics. He was asked to join them at supper at 9pm but declined “remembering the shortage of food for English families”.

The next morning, he walked down a stone-walled lane to School Road and the army mess in the “Quonset hut dining hall abutting a quiet stream. After breakfast, a walk through town to the bakery, a day’s work, return to the mess and then back to Allison Road” – his daily routine. But his return to his billet on his second day brought a big difference:

“On opening the [bedroom] door, imagine my surprise to discover the palliasse gone, in its place a bed with a fine mattress, sheets and coverlet. The window was surrounded by delicate curtains, a throw rug in the floor, a small table with chair held my few personal items. The room provided the adequacy and privacy of my home back in the States.”

If Eugene needed any further confirmation of his acceptance in this family, he found when he “discovered the family at supper with a vacant chair placed for his participation.” It was so different from the “cold reserve” he had expected from the English.

His relationship with the family grew more and more over the coming months. He described Nell as possessing “courage in a quiet and unprepossessing way” and “the serenity of peace even when the sirens were screaming”. However, when he managed to get tickets for Cinderella at The Hippodrome he could see the spontaneous and relaxed woman she must have been before the war.

With the father, Roy, he was able to discuss army life as Roy had previously served as a sergeant major in India until he was invalided out. He now worked at the U.S. Merchant Marine Club on Park Street and “never quite understood the casual approach of the Yank to the American Army”. He used to wake Eugene up at 7am with a very poor cup of tea: cool, weak and milky!

There was also Bryan who was just starting school and for whom he sought long and hard for a suitable birthday present. Finally, there was the “beautiful daughter, Jean, [who] was a quiet, intelligent lady of 12 with a great desire to learn.”

A routine was soon established: “Within a short time, I found myself coming home nearly every evening. Unless I was on duty or otherwise occupied, the family waited dinner for me if I was late. We gathered near the fireplace, the only room heated due to the shortage of fuel. The meal was served. As I had eaten earlier at the army mess hall, I had only a ‘spot of tea’ and sometimes a touch of dessert. It was difficult to believe I had left the States and was still in the army; I felt at home.”

The welcome Eugene received can, perhaps, be explained by a family tragedy. “There was an absent one who was seldom mentioned but whose presence was felt. The family had moved to Allison Road, their previous home having been bombed. The eldest son had been a casualty of the unreasoning logic of war; he was missed in quiet silence.” Roy even introduced Eugene as his son to the landlord of the local pub, ‘The Good Intent’.

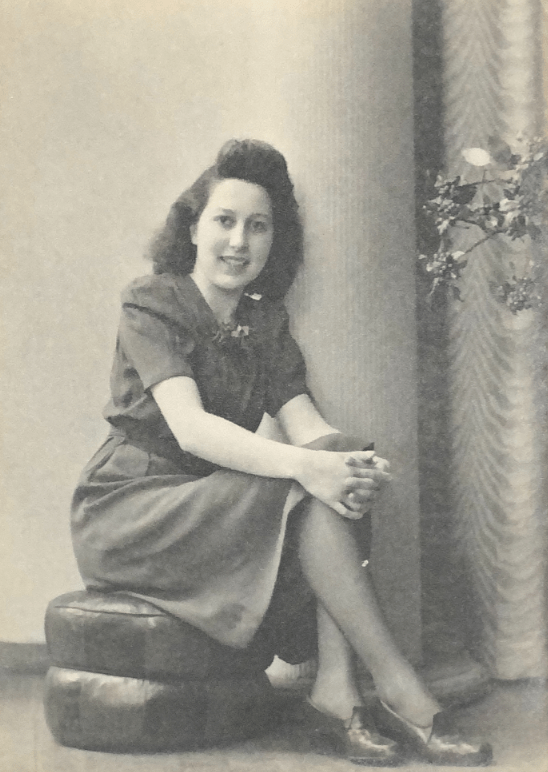

Eugene was also invited along to the weekly dance at the town hall. “The first evening was somewhat devastating due to the dancing” as he was not used to English folk. He did, however, meet a young lady named Gwen with whom he danced. When he asked to escort her home, she paused and said, ‘yes’ to which her friend retorted ’Remember our resolve not to date a Yank’!’ They stopped for fish and chips on the way home and it was all innocent. In fact, Eugene describes their relationship as a “delightful friendship” rather than anything romantic as they “saw movies, attended music hall, an occasional dance, had tea at St. Stephen in Bristol Square, and enjoyed long walks.”

“What of recreation?” asks Eugene. “Visiting Bristol became a frequent pleasure. The ride of the two-decker bus was an opportunity to view from its upper deck the diversity of the old city – old townhouses, streets of narrow row houses, industrial plants near railroad storage areas, pubs, quiet parks, all composing a kaleidoscope view.”

Other highlights included Christmas Steps, university and arts centres as well as “a walk on the Suspension Bridge, gazing at the river flowing serenely below gave one a moment of tranquillity”. He ensured he finished in a quintessentially English way by “having a spot of tea or a bite in a small café was looked forward to as each wandering came to an end”.

Eugene made the most of his time by touring the surrounding areas: the Roman architecture of Bath; the “ecclesiastical air” of Wells and Bristol suburbs “the names of Bedminster, Clifton, Fishponds, and others come to mind”. But his heart was very much in his adopted home of Brislington.

Soon the time came for the Americans to move out and set up headquarters in Normandy and Eugene’s departure was scheduled at noon six days after D-Day. He stopped at the house of a fellow G.I.: “The lady of the house opened the door and in tears informed me in a trembling voice that [her American lodger] had already left.” The Yanks were going to be missed.

On returning to his billet, he found Roy was there, exchanged small talk and was seemingly relieved that there wouldn’t be a big emotional farewell from his English family. “Slowly walking through the farmland to School Road, I turned for a last look at my home in England”. He was able to pop in to see Gwen before he left, “she slowly touched my shoulder, kissed my cheek and murmured, ‘Take care, we’ll miss you, Gene’. Another moment was etched in my memory.”

As he crossed the Channel for France, he was alerted to the Normandy hills “The distant sky was lighted by recurring flashes and a dim rumble of sporadic thunder could be heard. It was not a storm; merely the signature and sounds of war”.

It wasn’t long before he experienced battle in person. He doesn’t mention it in his memoirs but his war record shows he was struck by shrapnel from a German shell. Focussing almost entirely on his experience of England and its people, Eugene doesn’t talk about his journey through Europe but it ended up in hospital. In March 1945, he had toes amputated from one foot due to an injury sustained from accidental rifle discharge and in July that year he was invalided out of the army and sent back to civilian life.

Post War

Eugene returned to America and gained employment with the U.S. State Department in Washington D.C. The post required travel including a trip to Europe in 1948 so he “arranged for a holiday in Brislington.”

After visiting London, he boarded the train from Paddington and was assigned a compartment with four school girls returning from an outing. One thing particularly struck him about their conversation: “Not one mention of war was heard; their chatter and laughter contained no element of fear”.

From Temple Meads he took a taxi: “War destruction was still everywhere; people rushed about as before [but] few uniforms could be seen.” Turning into Allison Road he found everything largely unchanged with one exception: “A large sign read ‘Welcome home, Gene’”. He spent a very happy evening reminiscing, drinking tea and laughing with his “English family”.

Having been in touch with Gwen, he set out to meet her following his old route to School Road. Discovering his old mess hall had been removed meant it “brought back a street no longer desecrated by a symbol of war”. Gwen and he took one of their old wartime strolls where he learned of one big change: Gwen was engaged. If this bothered Eugene, he certainly didn’t mention it many years later when happily married himself. In any case, the three of them enjoyed a happy evening together at the Old Vic followed by fish and chips.

Once again he bid a sad farewell to Brislington and returned to Washington where he married his wife, Gerry. In the later 1950s, he left the diplomatic corps, becoming a financial director while becoming an accomplished fine artist in his spare time. He and Gerry retired to Phoenix, Arizona where he died in April 2001.

Post Script

In 1973, Eugene made an emotional return to a transformed Bristol with Gerry staying in the newly-opened Holiday Inn. His reflective story is shown in full here.

Further Reflections

Originally this story was written entirely based on the memoirs of Eugene Norton. However, following a story in the Bristol Times about this website, Jonathan Rowe of the Brislington Conservation & History Society contacted me with further information. Eugene’s memoirs had been given to the Frenchay Hospital Museum by Bryan Wilson himself. The original text used pseudonyms for the people involved but with the help of Jonathan and an April 2019 article in the Bristol Times, their actual names are now used (Gwen remains a pseudonym).

The story does have a sad twist. Eugene had played down his love for Gwen describing it as only ‘delightful friendship’. In reality he was in love with her and returned in 1948 hoping to propose but was too late. His marriage wasn’t a happy one as he had missed out on his true love.

Even More Reflections

Further contact was made by a very special person in this story, the daughter of ‘Gwen’! Her real name was Glenis and she lived at Nelson’s Glory and married in 1952. Glenis’ daughter very kindly provided the following photos.

We’d love to hear your own stories. Please get in touch with us by emailing YanksinBristol@gmail.com

Copyright © 2025 – YanksInBristol.co.uk – All rights reserved.